Black Founders. Black Investors. And the Pressure to Get It Right.

We’re not looking for charity, we’re designing new conditions for success

I’ve been wrestling with something.

We all say we want to support Black businesses.

We want Black founders to get funded.

We want Black investors to circulate capital within our communities.

But when you zoom in on what it actually takes for that to work—it’s complicated.

The Tension Nobody Talks About

On one side, you’ve got Black founders—the least funded group in venture.

In 2023, Black founders received just 0.48% of all venture capital. That’s about $661 million out of $136 billion.

And most don’t have a network of family and friends who can float them through that first stretch. They’re bootstrapping, side-hustling, and navigating gatekept rooms just to get a shot.

On the other side, you’ve got investors who are Black—many of whom are first-generation wealth themselves. Often locked out of legacy VC networks. Sometimes brought into the riskiest deals simply because someone “let them in.”

That’s the paradox:

You’ve got people with limited capital being asked to back businesses with limited support.

It’s not a bad idea—it’s just an underfunded one.

What Comes First—the Chicken or the Egg?

I’ve heard the frustration from Black founders:

“Why don’t Black investors put more money into us?”

And I get it.

Because if you’re building something with heart and vision, it can feel like your own people are sitting on the sidelines.

But here’s the hard truth: most of us are building without a safety net.

In the early stages of a startup, most founders lean on their networks to get through the messy middle.

The “friends and family” round is where companies survive, or stall out.

But that’s where our community hits a wall.

A study by the Kauffman Foundation found that during their first year, white founders raised an average of $20,682 from their networks.

Black founders? Just $976.

To match that same early support, a Black founder would have to pull from more than 20 families just to match what one white founder might raise from their inner circle.

That’s not just a funding gap. That’s a generational wealth gap showing up in real time.

So yes, Black businesses need Black dollars.

Especially in the beginning.

Because if we don’t show up early, we’re rarely there at the exit.

But that’s also what makes this so hard:

We’re asking first-generation wealth to take first-in risk on founders who haven’t been given the tools, access, or room to get it wrong.

It’s not about blame.

It’s about recognizing the structure and deciding to build something better anyway.

The Missing Link: Groups Like Camelback Ventures Matter

In early 2025, I attended the Culture Shifting Summit in Miami—a gathering designed to catalyze deals and collaborations among diverse entrepreneurs and investors. There, I sat down for a fireside chat with Shawna Young, CEO of Camelback Ventures, to unpack one of the most intriguing tensions in business today: the gap between Black founders and Black capital.

The conversation hit hard.

Because it’s one I’ve been wanting to have publicly for a long time.

Camelback Ventures was founded by Aaron Walker, a former educator and lawyer who saw how genius was often overlooked simply because it didn’t come wrapped in the right packaging. His mission? To invest in underrepresented entrepreneurs at the earliest, most critical stage when the ideas are sharp but the infrastructure isn’t there yet.

That’s the bridge.

They step in at the pre-seed level, when most traditional investors wouldn’t even return an email.

They help entrepreneurs of color refine their models, tighten their pitches, and build the kind of operational foundation that gives investors real confidence.

They don’t just write checks.

They write playbooks with you.

And those playbooks turn overlooked potential into fundable, scalable businesses.

That’s what makes Camelback different: they’re not just helping Black founders look the part , but they’re helping them become the part. Structurally. Strategically. Intentionally.

This isn’t about “investing in anything Black.”

That’s not strategy—that’s sentiment.

We invest in businesses.

The fact that the founder is Black? That’s the focus. That’s the mission. That’s the impact.

But the business still has to stand.

Organizations like Camelback make that stand possible.

Because they know the truth: If we don’t show up for our founders when no one else will, there may not be anything left to show up for later.

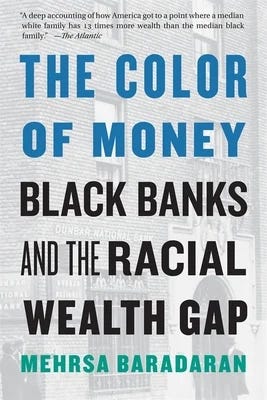

A lesson from black banks

It reminds me of the struggles Black-owned banks face when trying to serve low-income communities.

They’re undercapitalized.

They don’t have the assets under management to provide the level of service high-net-worth individuals require.

And so they get stuck in a loop where the communities that need them most are the hardest to serve profitably.

That’s the cycle.

And we can’t fix it by pouring money into broken systems or abandoning the mission altogether.

The Fearless Fund: When the Rules Move the Goalposts

It’s easy to say “we just need to invest in each other.”

But the truth is, that alone isn’t enough.

Because we’re not just building businesses—we’re building inside a system that’s not designed for us to win.

So we have to support each other in a way that can survive the context of the times.

Look at what happened to the Fearless Fund, a venture group created specifically to invest in Black women entrepreneurs by serial entrepreneur, philanthropist, angel investor, author, and PR & marketing specialist Arian Simone.

They weren’t handing out charity. They were investing in overlooked potential with intention and structure.

And still, they were sued.

Forced to suspend their grant program.

After a court ruled that their support for Black women was… discrimination.

If that doesn’t tell you how much resistance there is to us even trying to level the field, I don’t know what does.

This moment requires more than alignment. It requires strategy that holds under pressure.

What We Can Do

We need a new model. One rooted in:

• Prepared founders with more than ideas — structure and strategy.

• Investors bringing more than capital—bringing networks, skills, accountability, and time.

• Support systems like Camelback Ventures that help founders cross the bridge from vision to viability.

• Long-term infrastructure, not just short-term hype.

And we have to make one promise:

We don’t quit on each other.

Final Thought

This mission isn’t clean. It’s not easy. But it’s necessary.

We may not have as many shots.

But the few we do have?

They deserve alignment. Intention. And infrastructure that gives us a real chance.

We can’t afford to operate like venture tourists—dropping in and hoping for a unicorn.

This work is deeper.

It’s about betting smart. Betting together. And betting forward.

What do you think it’ll take to build a better system for both Black founders and Black investors?

Drop a comment. Share this with someone who’s in the arena.

We’re not just talking capital, we’re talking trust, alignment, and legacy.

Sources

Kauffman Foundation Study

White founders raised an average of $20,682 in non-owner equity funding during their first year, while Black founders secured only $976.

→ TechCrunch: 'Friends and family' funds could help Black foundersCrunchbase Diversity Report (2023)

In 2023, Black founders received just 0.48% of all venture capital—approximately $661 million out of $136 billion.

→ Crunchbase News: Drop In Venture Funding To Black-Founded Startups Greatly Outpaces Industry DeclineFederal Reserve / Brookings Institution on Racial Wealth Gap

In 2019, the median wealth of white households was $188,200—7.8 times that of Black households at $24,100.

→ Brookings: The Black-white wealth gap left Black households more vulnerableFearless Fund Legal Proceedings

The Fearless Fund was sued and forced to suspend its grant program for Black women entrepreneurs.

→ NPR: Fearless Fund grant program is discriminatory, appeals court rules