As a man is, so he sees. As the eye is formed, such are its powers.

— William Blake

The Privilege of Space

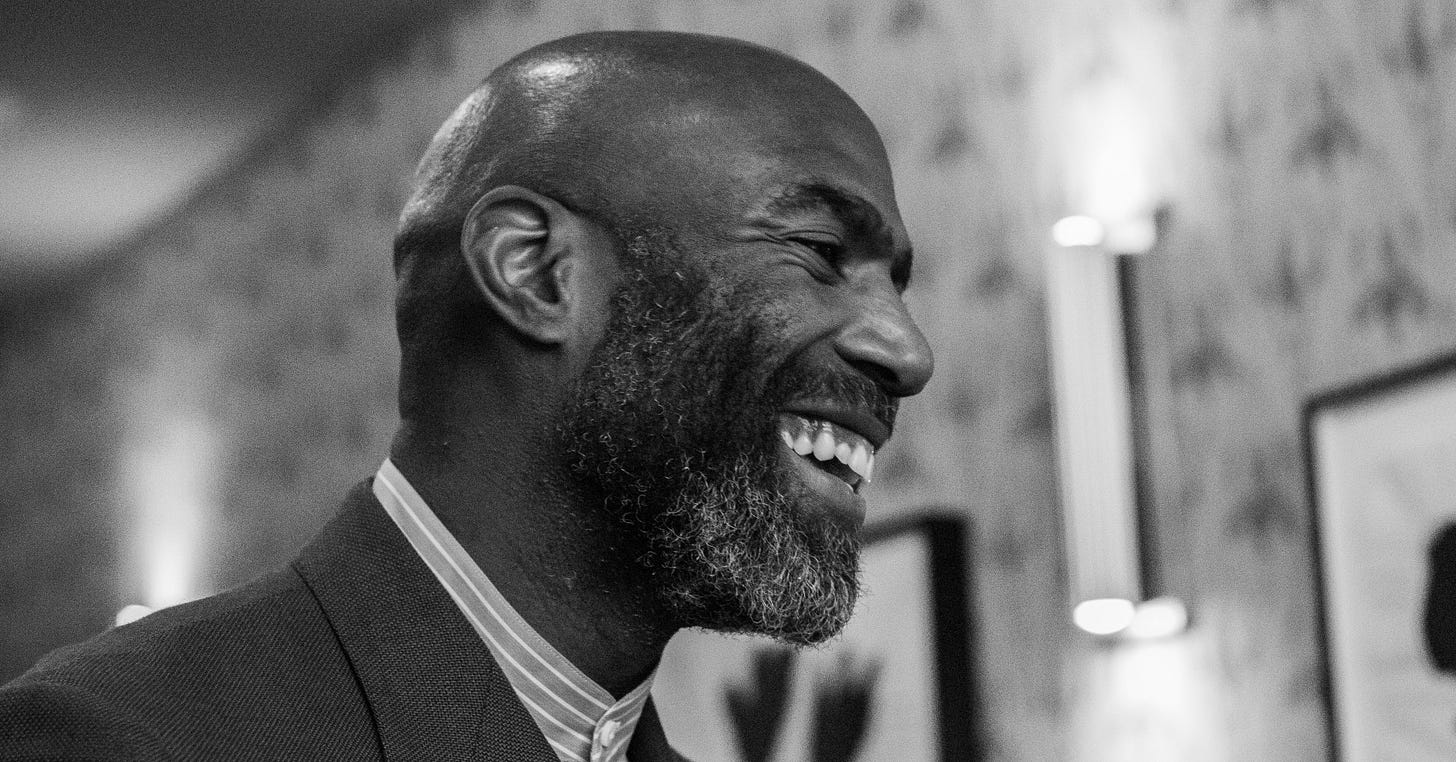

As I write these words I am a 37 year-old black man, retired after what many considered a lengthy career. I’ve come to understand just how fortunate and privileged that makes me.

Right now, millions of Americans with longer careers than mine can’t afford to retire, even at the age most of us dream about. Even among athletes, I belong to a rare group who chose when to walk away. Most never get that choice; being forced out by decline in ability, injury, or someone else’s decision.

I gave blood, sweat, tears and years of my life to the game. I made sacrifices, took risks, and stayed disciplined. But even with all of that, I recognize the gift I’ve been given: space. I no longer have to chase the next check or survive the next season. I get to ask myself what I want—and answer that honestly.

What I want, what I need, is to create. I don’t see retirement as a place to kick my feet up and rest, but as a new life: one with bigger dreams, sharper focus, and the freedom to shape it on my own terms.

This is the new privilege. Not to rest, but to reinvent.

New Vision

Lately, I’ve been sharing my love for photography on social media, popping up at NFL and college games, and documenting my journey as I learn more about the craft and the art of seeing.

As an NFL safety, I spent the majority of my 13 year career honing my ability to see beyond the obvious.

My favorite defensive mind, Greg Williams, told us:

“Before every snap, the offense is telling you a story. Can you read it?”

Every play came with clues —if you know where to look. My ability to see those indicators, process them quickly, and communicate them out to my teammates is part of what made me so valuable. Greg trained us like artists, teaching us to see beyond what’s on the surface and lock onto what matters most.

To see the game—or life—in this way, you have to first know what to ignore. Another Gregg Williams mantra was:

“A coach who can’t tell you where to put your eyes is full of shit.”

What you look at will determine what you do. See everything and you’ll see nothing. See a little, and you’ll see it all.

Take pre-snap reads: conventional wisdom says you study offensive personnel, formation, down and distance, field position, and any tendencies you can remember about the offensive play caller. But often, the play doesn’t announce itself through the formation. It whispers through a running back’s glance, a lineman’s lean, or a twitch in the slot receiver’s stance. The game, for those who know where to look, is often that simple.

My eyes mattered more to my game than any physical attribute. Once you train your eyes to recognize what matters, everything else fades into noise.

How I See It Now

When I stepped away from the game, I finally had the time to lean into my love for art. What began as collecting quickly turned into creating. I had to learn what separates an iconic image from a forgettable one.

It’s not just who’s in the frame.

Recognizing a great photograph requires you to see where the light and shadows fall, how the overall composition sits, and how the color and temperature interact with each other. It requires an awareness of body language and imagining how to bring into context what might exists just outside of frame.

To be a decent photographer, you must develop your eye. You must look at a scene and decide, in the moment, what’s worth capturing and how best to capture it.

With a camera in hand, I found myself applying the same vision I’d sharpened on the field. Only now, it wasn’t to diagnose a play—but to preserve a moment.

And that same skill, seeing clearly, filtering noise, serves me in nearly every aspect of life: evaluating my team, making investments, or identifying risks.

So, if you see me out with my camera, know this: I’m still training my eyes.

The Story About The Story

Artists become icons when they can present a new perspective on a familiar narrative or story. The iconic artist isn’t defined by any individual piece, but by a body of work and the stories that surround it.

My editor and friend Yahdon puts it this way:

“Icons don’t tell the same story over and over. They continue to unpack new stories about the story that has already been told.”

This new version of myself feels that pull: to tell the story about the story. To bridge the gap between what I was known for and what I’m building now.

I have fully accepted that my playing days are done, and have no desire to relive those experiences. Instead, I’m working to repurpose sports as a framework for teaching. It’s the language I know best, and I am learning to translate it into universal insight that is practical, useful and unique. A place to express my vision and insight in a way that doesn’t box me in, but continues to expound on my story.

People often ask why I didn’t go into coaching or broadcasting. It’s a fair question. I’ve spent my entire life studying the game from every angle. But I didn’t want to jump into another system. I wanted space. I wanted time to grow. I needed to spend the first few years away from the game so that I could come back to it with new vision and refreshed interest. Distance from the game gave me room to explore myself, and ultimately return on my own terms.

Through my camera’s viewfinder, I’ve found a fresh way to observe. I now notice things that I missed as a player: the machinery of the business behind the scenes, the individual faces in the crowd, the tension between teammates after a mistake.

The game hasn’t changed. But how I see it has. And that’s changed everything.

Lets Talk

Where in your life are you training your eye? What are you learning to see differently now?

Dope!! Love your work!! Go Birds!! 🦅